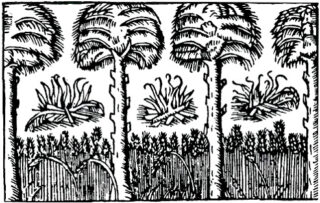

Out of the ashes that is left after the burning of peat, bushes and sticks a remarkable fertility now arises, so that especially if you therein sow winter rye, beets, poppy, flax or hemp, a rich and plentiful harvest is generated.

Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, 1555.

Svedjebränning in Tuovilanlahti, Finland, 1928

All grounds and soil for crops ideally need to be prepared before sowing. One method common already in the medieval Scandinavia was Nordic “Svedjebruk”, a variant of Slash & Burn cultivation said to originate in Russia and arriving to Scandinavia via Finland some time in the Viking period or the Middle Ages. Consequently in Sweden it was at first most common in eastern Sweden, today’s Finland, and later among the “Finns” that migrated to Western Sweden in the late Middle Ages.

The method means forests, often pine or spruce forests, which commonly grow in already rich soil, were transformed into 3-year crop fields for rye, barley and beets through burning. It was highly effective and 1 litre of seed could give 100 litre in return, while regular fields would normally give a 4:1 return. Modern amateur testing have shown this to be correct and seemingly even an underestimate.

Svedjebränning in Eno, Finland, 1893

Svedjebränning, from Olaus Magnus’ Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus of 1555.

The preparation involved first cutting away all branches of the trees, as far as you could reach, and stripping the bark in a ring around the tree to let the tree die and dry up. The following year the trees were chopped down and after drying during the Summer the trees and ground were burnt. The soil was then turned over and mixed with the ashes thereby making it even more fertile.

According to some older sources (Norlind, 1912), beets were first planted, in the first summer after the burning, and they were unusually large and sweet. Towards Fall Winter Rye was sown and the year after gave tall rye. The third year no sowing was done and instead cattle and horses were allowed to graze the field.

Current sources claim that rye was planted first and beets in the second year and one reliable source (Bergholm, 2013) describe two methods used by the Finns; Huuhta and Kaski.

Huuhta was used on mature pine or spruce forests or mixed forests with e.g. spruce, birch or alder. The trees were felled in early Spring and were left to dry for two years before they were burned in July on the third year. Rye was sown as quickly as possible into the ashes without plowing or mixing the soil. This method was especially common in Savolax and for a yearly harvest of rye it required four fields in different stages. Spruce and pine would only grow back fully after 80-100 years if the fields were left to grow wild. More commonly, dedicious forests grew back in a few decades.

Kaski was used for young decidious forests of 15-30 years, commonly forests growing on former slash-and-burn fields. The trees were felled around midsummer or early Fall and burned the next Summer. Autum Rye was sown and could be harvested the following year. Barley could also be sown and then harvested the very same year.

Beet seeds are said to sometimes have been sown by placing oneself in the middle of the burning, putting the seeds in your mouth and then blowing them in all directions. This worked particularly well if you had a dry mouth. (Levander, 1947)

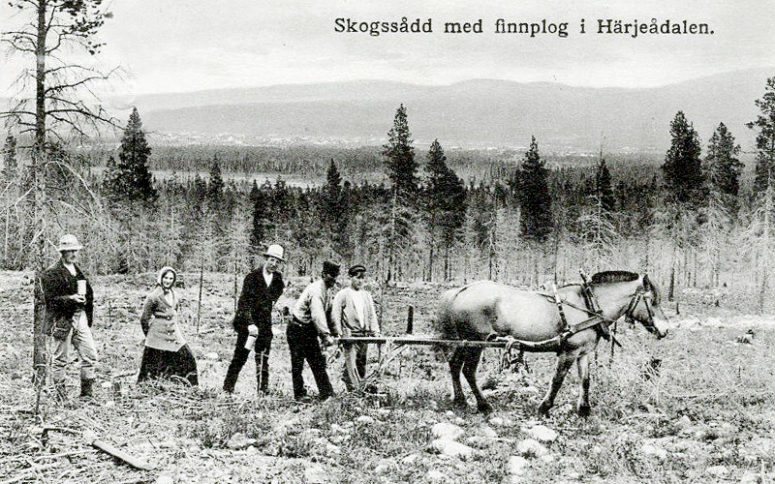

Sowing in forest using “Finn Plow”, in Härjedalen, Sweden 1915.

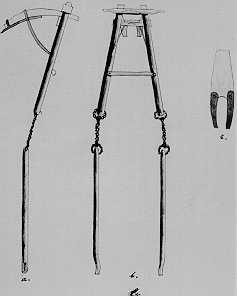

Traditional Finnish forest plow, known from the 18th cent. and onwards. Designed especially for rocky fields and made to easier jump over large stones.

Although giving good crops these methods made the soil unusable for seed growing for one or two decades while the trees grew back. Consequently new fields needed to be created every year. Similar methods were used already during the Neolithic revolution about 12,000 years ago, but for the reason given above it has often involved using up the soil and thereafter a forced relocation, leading to a nomadic life. This nomadic slash-and-burn method is also known to have existed in the Nordic countries as early as 5,000 years ago.

Naturally this also consumed large areas of forests, and with that only the sparsely inhabited areas of the Nordic countries came to have any larger wild forests after the Roman era, for which reason the method would only see any wider use there. The particular Nordic Svedjebruk however, usually meant a fixed dwelling and instead travelling long distances to the fields in different stages of development. However, with a growing iron and wood industries, producing timber, charcoal, tar and turpentine for carpentry, house and ship building & maintenance, the method eventually became controversial. Already in the mid 1600s the state tried to outlaw the use of Svedjebruk in certain regions, but the method was still in use in the 1930s.

For a long time, the method has been regarded as outdated and ill-reputed, probably largely due to the interests of the powerful forest industry, and this can probably also be seen in the painting “Trälar under penningen” (Slaves under the money) by Eero Järnefelt shown at the beginning of this article, where the wretched Finns are burning the forests trying to scrape out a living, although it was painted during particularly bad years with crop failures and starvation in all of Finland. But given the fact that you get a 25:1 return instead of a normal 4:1, the method is still more effective than regular soil preparation, even over a 10-20 year period where only 2 years are effective growing of crops. With quick growing trees you would get twice as much return and slower ones still a 20% higher return. Alternately, smaller areas of land can of course also be used, shifting area over the 12-20 years. And if you had access to enough land you could have several highly effective fields going simultanously, which is how the Huuhta method worked, keeping four fields in different stages at the same time.

The practice also spread to New Sweden in North America, further reinforced by the use of fire in agriculture and hunting by the Native Americans and with this also adding Indian Corn to their farming. The Huuhta-Finns are known to have travelled large distances regularly, not least in winter time, seeking new prospective farm land, but this shouldn’t be confused with the older nomadic slash-and-burn farming. The Finnish-Swedish settlers also brought with them the traditional forest house design, the log cabin, that would become so popular among settlers of North America that it today is thought of as an American iconic design.

Today svedjebruk is still used in the Nordic countries, albeit rarely and under restricted and controlled circumstances. Done with proper restraint it can be a good method, but it requires allowing the area to rest properly. Slash and burn cultivation is also commonly used in parts of Africa, South America and South-East Asia, although it is not as effective as the svedjebruk in the Nordic countries, and more commonly as a means of transforming forests into farming grounds. Still, the method of slash-and-burn for shifting cultivation is again gaining popularity and respect as a sofisticated farming technique as it is becoming better understood through modern recreation.

References

Bergholm Hanna, 2013 Minne och livsmönster, Bachelor thesis at Lund University

Hoffecker Carol, 1995, New Sweden in America, University of Delawere Press

Levander L. 1947. Övre Dalarnas bondekultur I – III. Stockholm

Lindqvist Herman, När Finland var Sverige, 2013, Albert Bonniers Förlag

Norlind Tobias, 1912, Svenska Almogens Lif i Folksed, Folktro och Folkdiktning, Bohlin & Co, Stockholm

Nyström Sören, Svedjebränning i Källslätten, 1998, Trollius periodical

Pajusi Arvo, 1998, Härjulfs Mat, Rapport 1998, Institute for Ancient Technology