I love Mora knives. There, I’ve said it. I know not everyone agrees to their greatness, but I grew up with Mora knives being the only knife everyone used, outdoors, in the garage, at school woodwork class, at work, literally everyone, and everywhere. I love them. And since I travel a lot internationally, and since some years back, I try to always give away Moras to new friends around the world, just last week even in South Africa. I’ve sort of ended up an unofficial ambassador, it seems, passing on the joy of these simple knives. Why do I do this? Well, I will try to explain why, but to do so, I first need to give some context.

The smaller a culture is in number of people, the more uniform they tend to get, and their habits and customs will continue to shape things for millennias to come. Looking back through the centuries of Nordic history, the region was quite barren, and even today it is a fairly sparsely populated part of the world, despite being big enough to cover some 10-12 states on the East Coast of the US. Sweden today still has less than 10 million people, just a little more than New York City or London, and going back further, to 1570 it was a mere tenth of that, and in the middle of the 1300s half that again, with only 600,000 thousand people. At the height of the viking period, Norway is estimated to have had only some 80,000 people, a sixth of the contemporary Danish and Swedish populations. And out of this, by today’s standards, ridiculously small number of people, quite a few habits and customs were formed and still to this day remain, passed on over the generations.

The design of tools is part of this and depends on both the tasks they needed to fulfill, the environment and climate they were and are used in, technological discoveries, as well as in priorities rooted in tradition. Looking around the world we see many different traditional designs e.g., the Malay parang (simply meaning “knife), the Nepalese kukri, the South East Asian Karambit, the Filipino Bolo, the US Bowie knife, the Spanish Navaja, the Scottish dirk, and the Canadian Belt Knife, just to mention a few of the many unique designs originally coming from small tribes and communities and their particular needs.

These traditions still go deep into the consciousness of the population, often used for a variety of daily chores, like carpenting, food preparation, skinning and gutting game, handling firewood, and they live on even in military tradition, where the classic Ka-Bar is quite reminiscent of the classic Bowie knife, with Spanish soldiers carrying modern Bolo knives in both WW2 and today, and with Norwegian soldiers commonly still carrying the big Leuku, while Finnish troops more commonly have carried the smaller Puukko and with their Special Forces being given the Peltonen Sissipuukko, just like Swedish ones always carried the classic Mora knife, even with pilots being handed a simple “survival” version of the same, all the way up until the 1990s, after which they instead are given the small Fällkniven F1 knife.

Simply put, cultures and nations come to identify with their things, and knives are a strong part of this, part of our very identity, even. Until fairly recently there were very, very few men born in Sweden who had never used a Mora knife already as a child, and certainly during the obligatory military service, and then most commonly using the classic, cheap red-handled model.

It is a uniquely iconic knife, one of the most iconic of all Swedish mundane objects, instantly recognizable to all Swedes, and attached to memories going decades back, to deeply cherished memories of, as a child, being given the first trust to learn to use a razor sharp knife and the pride and the tingling pang of fear associated with it, to memories of cuts, blood and tears, but also of carving hot dog sticks with family and friends, of log fires by some lake in endless summer nights, and to memories of happiness and excitement while gutting your newly caught fish and frying and eating it shortly after, and to countless other magical moments that stay with us until we die, shared over many, many generations who can relate with similar memories of their own. All of it revolving around a single focal point; the birch-handled Mora knife.

And it stretches back in time. My father had Moras, my grandfathers did as well, and their fathers, and so on going back many generations, and beyond that an endless line of people stretching back at least a millennia, using knives of very similar designs, all of them going through very similar experiences as young boys, and thereafter carrying and using them for the rest of their lives. And my two sons, of course, both have theirs, as I hope will their offspring too one day, continuing the tradition and practice.

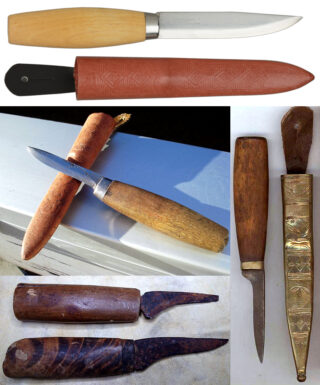

Doubtlessly, the classic Mora knife, with its typical Scandi Grind, and its simple handle and sheath has stood up well to time, with no need to change it in any way. While not cool or fancy, it is a good, sharp knife that performs excellently in the various tasks it is intended for, and is accessible to everyone since it is still a quite cheap knife. All of these things together explain why it has become such an icon in the consciousness of the Swedes, and lately also has again become very popular overseas, not least among outdoors people who have rediscovered the Swedish Moras.

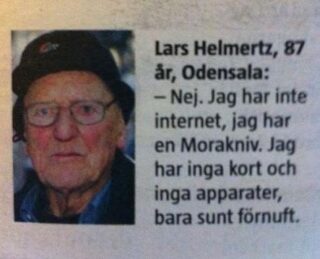

“No, I don’t have Internet, I have a mora knife. I have no cards or apparatus, just common sense.” – Lars Helmertz, 87 years, Odensala

Still, as the world changes and these items, so deeply rooted in the needs and customs of the people who designed them, spread and are used by people of a different tradition, the understanding of them do not always accompany this, meaning users are sometimes surprised by the properties of them, sometimes in a good, sometimes in a less good way. Scandinavian knives, e.g. are by many Americans often regarded as surprisingly sharp, but their rat tail tang is argued by some to be bad, since you “can’t baton safely with such weak” tangs, a habit not seen in Scandinavia until the last decade or so, and which the knife type simply isn’t designed for. A habit that also doesn’t seem to stretch particularly far back in time, even in the US.

Originally, these knives were designed to be used in a variety of grips, for hours on end, six days per week, even in wintertime and without gloves, thus the hidden “rat tail” tang and the oval barrel shape of the grip. They were made to be easy to regrind, so you could grind and sharpen it with a simple whetstone, but with its laminated steel still being durable enough to not break in the blade from hard use.

Originally, these knives were designed to be used in a variety of grips, for hours on end, six days per week, even in wintertime and without gloves, thus the hidden “rat tail” tang and the oval barrel shape of the grip. They were made to be easy to regrind, so you could grind and sharpen it with a simple whetstone, but with its laminated steel still being durable enough to not break in the blade from hard use.

They were designed to be used, cared for and then disposed of, replaced with a new one, so commonly no frills or fanciness, even skipping leather for the sheath, replacing it first with “vulcanised fibre” and later with plastic. It was a knife designed to be a people’s knife, an all-purpose knife that everyone could get, and you have to understand all this context, to understand the design and value of the Mora knife, and the heritage it brings with it into modern time.

So, I hope I here have managed to explain how the Mora knife means more than just a knife to me, and why I give them away to foreign friends when I can. They carry meaning, tradition and culture, and memories of many, many lives and generations in the North. I only regret I can’t give away more of them. I still have so many friends to bring into this part of history.