George Washington Sears (December 2, 1821 – May 1, 1890), might not be so internationally famous, but among American bushcrafters he is without doubt one of the most well-known and influential early fathers of the whole lifestyle, inspiring other renowned outdoorsmen like Horace Kephart, and his works continue to be read and reprinted, but also disputed and debated.

Sears was born on Dec 2 1821 outside of Oxford Plains (now Webster), Massachusetts, between the Nipmuck Pond and Junkamaug Lake in the South Gore (now Kingsbury District). He grew up as the oldest of 10 children. At the age of 8 he began working at at a saw mill owned by a Samuel Slater on the orders of his father. He quickly ran away and at 12 he started working as a fisherman at Cape Cod where his grandmother lived. At 16-19 he then spent three years as a whaler on the whaling ship Rajah sailing from New Bedford. His whaling years ended badly though, having been put ashore with bad fever in Feyal Island in the Azores off the shore of Portugal. He spent several months in fever, before being sent home by the American Consul. He also worked as a teacher, as a “bullwhacker” (an ox cart driver), a silver miner and cowboy, before ending up a shoemaker like his father, in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania in 1848.In the 1850s he was contracted to hunt and supply railroad workers with meat in Michigan, employing local Chippewas to assist him. Between 1852-53 he went on a trip from Saginaw Bay to Muscegon River with a companion, Ned Miller, who soon got homesick and after a quarrel left Sears to stay alone in the harsh winter. Sears did well for a few months but eventually became seriously ill, unable to sustain himself. He was later discovered and rescued by his Chippewa guide who brought him back to the tribe in spring and nursed him back to health.

Sears was born on Dec 2 1821 outside of Oxford Plains (now Webster), Massachusetts, between the Nipmuck Pond and Junkamaug Lake in the South Gore (now Kingsbury District). He grew up as the oldest of 10 children. At the age of 8 he began working at at a saw mill owned by a Samuel Slater on the orders of his father. He quickly ran away and at 12 he started working as a fisherman at Cape Cod where his grandmother lived. At 16-19 he then spent three years as a whaler on the whaling ship Rajah sailing from New Bedford. His whaling years ended badly though, having been put ashore with bad fever in Feyal Island in the Azores off the shore of Portugal. He spent several months in fever, before being sent home by the American Consul. He also worked as a teacher, as a “bullwhacker” (an ox cart driver), a silver miner and cowboy, before ending up a shoemaker like his father, in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania in 1848.In the 1850s he was contracted to hunt and supply railroad workers with meat in Michigan, employing local Chippewas to assist him. Between 1852-53 he went on a trip from Saginaw Bay to Muscegon River with a companion, Ned Miller, who soon got homesick and after a quarrel left Sears to stay alone in the harsh winter. Sears did well for a few months but eventually became seriously ill, unable to sustain himself. He was later discovered and rescued by his Chippewa guide who brought him back to the tribe in spring and nursed him back to health.

He also served briefly as a sergeant in the Civil War in 1861 in The Bucktails Pennsylvania regiment of backwoods’ sharpshooters, but was relieved of duty due to broken foot before he had a chance to engage in battle. He reportedly travelled widely in the US, living under simple circumstances in Ohio, Colorado, Missouri, Minnesota, Texas, Oregon, Michigan, Florida and even travelled up the Amazon river in Brazil twice on a rubber business venture. His camping trips though, seem to mostly have been restricted to trips around the Adirondack lakes, upstate New York. That said, he himself estimated having spent a total of 12 years of aggregated time camping.

Under the name Nessmuk Sears wrote about his observations on nature and outdoor life for Spirit of the Times and the Atlantic magazines in the 1860s and for the Tioga County Agitator in the 1870s. He took his pen name from a native American friend of the Nipmuc tribe,who in Sears’ younger years had taught him many of his hunting, fishing and camping skills. In 1880, at the fairly old age of 59, suffering from acute pulmonary tuberculosis and having read William Henry Harrison’s ‘Adventures in the Wilderness’, he decided to pick up on the latter’s claim that the North Woods was a good health resort for those who suffered various health issues and thus set out to the Adirondack lakes, hoping to restore his health.

Having taken three trips in 1880, 1881 and 1883 he consequently retold his experiences from them in Forest & Stream magazine under the pen name Nessmuk, and his letters instantly became very popular. Sears wrote his only book, Woodcraft & Camping, in 1884 and it was an instant success serving as a basic guide into outdoors life.

He is often considered to be the father of ultralight packing as he advised packing only the most necessary gear, which is a topic that has been contested as to its actual meaning. He advised his readers to ‘Go light, the lighter the better’. That said, his light packing would probably still be considered heavy by today’s standards and one can wonder how far his stance on this topic would have extended. Furthermore, going through his packing lists and what he describes bringing along, his packing seems to be fairly heavy, again by modern standards, and the low numbers do not always seem to include everything he would have brought along, more giving a picture of intent, of what to strive for, within the boundaries set by need, necessity and opportunity. It should also be taken into account that he had health issues and was a small man, about five feet four inches tall and weighing about 110 pounds, which would have forced him to pack light.

He is often considered to be the father of ultralight packing as he advised packing only the most necessary gear, which is a topic that has been contested as to its actual meaning. He advised his readers to ‘Go light, the lighter the better’. That said, his light packing would probably still be considered heavy by today’s standards and one can wonder how far his stance on this topic would have extended. Furthermore, going through his packing lists and what he describes bringing along, his packing seems to be fairly heavy, again by modern standards, and the low numbers do not always seem to include everything he would have brought along, more giving a picture of intent, of what to strive for, within the boundaries set by need, necessity and opportunity. It should also be taken into account that he had health issues and was a small man, about five feet four inches tall and weighing about 110 pounds, which would have forced him to pack light.

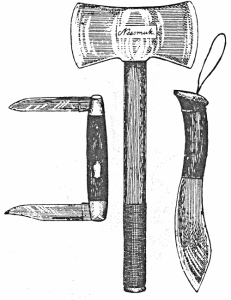

Sears’ favorite tools: a two-bladed folding knife for carving, a custom made hatchet with different grinds on the two sides, and a thin-bladed hunting knife for food preparation and eating

Through his writings he popularized lightweight canoeing in the Adirondack lakes, having designed his own type of canoes together with the builder J. Henry Rushton, canoes which weighed a mere 10-17 pounds – a fraction of the standard contemporary canoes and guideboats. This approach to canoeing lives on to this day all over the globe with quite light canoes, even inflatable canoes. These light canoes is what he used to travel alone 550 miles in the Adirondacks in the summer of 1880, and also on the following trips.

Sears is also seen as an early environmentalist & conservationist and his writings reveal both a concern and a profound sadness for a world that was quickly disappearing and already had disappeared in his lifetime due to widespread exploitation of the wild with cut down forest and disappearing hunting game.

Sears can be seen as a man of his time with many men longing for a return to a more ‘natural’ life, wishing to escape the stress of urban life, with a lineage from Jean-Jacques Rosseau, passing to e.g. American Henry David Thoreau and Swedish Carl Jonas Love Almqvist in the first half of the 1800s. However, although having a strong love for nature, he was under no illusion as to its harshness and potential brutality. His outlook on it was far from romantic and instead quite down-to-earth.

…and there be some who plunge into an unbroken forest with a feeling of fresh, free, invigorating delight… These know that nature is stern, hard, immovable and terrible in unrelenting cruelty. When wintry winds are out and the mercury far below zero, she will allow her most ardent lover to freeze on her snowy breast without waving a leaf in pity, or offering him a match; and scores of her devotees may starve to death in as many different languages before she will offer a loaf of bread. She does not deal in matches and loaves; rather in thunderbolts and granite mountains. And the ashes of her camp-fires bury proud cities. But, like all tyrants, she yields to force, and gives the more, the more she is beaten. She may starve or freeze the poet, the scholar, the scientist; all the same, she has in store food, fuel and shelter, which the skillful, self-reliant woodsman can wring from her savage hand with axe and rifle.

That said, his writings are clearly aimed at a Victorian era audience, and more specifically working men with less means and little experience of outdoors life, which influences his topics. Furthermore, the woods where he travelled were quickly becoming civilized with easy railroad and steamboat transport, and wilderness hotels and supply stores to satisfy the booming camping and hiking business. Sears too took advantage of these and even worked together with them supplying meat and firewood, but he still maintained a pragmatic view on things that in spirit is valuable even today. And in many ways his actual advice is still quite useful, with regards to how to think and behave.

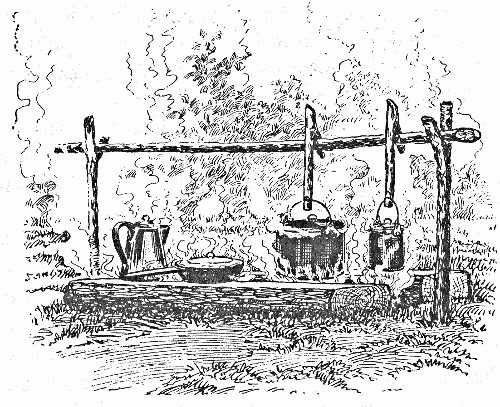

Camp fire for cooking for a more permanent base

In other ways it is outdated as it doesn’t quite fit the modern world with regulations on how you are allowed to use material like trees in the woods. For example, he regularly cuts down 2-3 one-foot hemlock trees for every camp he sets up and relies on hunting deer for sustenance, even letting leftover game meat rot away, having caught more than needed. That said, he also states that is not a good thing to do, but other wildlife would quickly consume the cadaver, thus meaning it would not be completely spoilt.

Small camp fire with heat reflector

At the same time his attitude was different to what was common in his time, with growing tourism and weekend hiking from commercial and fixed camp bases. He stated “We do not go to the green woods and crystal waters to rough it. We go to smooth it“. This can be interpreted in different ways, but combined with his other expressed thoughts and ideas, a likely interpretation is that it reflected the idea that you should aim to be comfortable, but do so in a manner that worked together with nature and not in opposition to it or as a direct disturbance in it. We should also keep in mind that especially in his youth, individual people still left a comparatively small imprint on nature with a national population of about a sixth of today, and trees and wildlife were still overabundant, thus allowing acting in a way that today seems wasteful and unnecessarily damaging.

Others criticize him based on anecdotes claiming he never walked far on his hikes, but there is no greater value in walking long distances than there is in building a camp and staying there or travelling rivers and creeks by canoe, and we would do well in remembering that his time was very different, with simpler equipment, no cars or electronics, no plastics and even quite sparse railroads before 1860, leaving horse, feet and boats & canoes for travelling. Still, he was just a man, and that is quite enough.

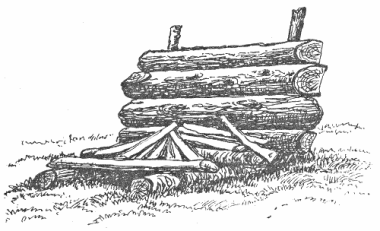

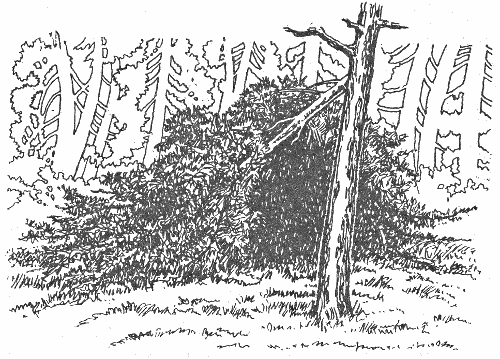

Simple “Indian” shelter as it is still taught for survival today

Woodcraft & Camping is a nice read if sometimes somewhat contradictory reading. This is natural as it tries to capture his 50 years of being an outdoorsman and contains general advice on camping, including how and what to pack, how to set up camp, how to make fire, cook food, recipes, tips on fishing and more. Generalization always leads to contradictions.

To myself I sometimes appear as a wild Indian or an old Berserker, masquerading under the guise of a nineteenth century American. When the strait jacket of civilization becomes too oppressive, I throw it off, betake myself to savagery, and there loaf and refresh my soul.

– – –

I love a horse, a gun, a dog, a trout and a pretty girl. I hate a pothunter, a trout-liar and a whiskey-guzzling sportsman. I smoke and take an occasional glass of wine and never lie about my hunting and fishing exploits more than the occasion seems to demand.Letter to Forest and Stream, published in 1918, after his death.

The humorous tone of the writing is often entertaining, but it can sometimes seem a bit too self-congratulating, ridiculing young and less experienced men, even naming names. At the same time his sadness and frustration with how the world has changed is quite apparent. He was a strong opponent of the lumbering and tanning practices of Pennsylvania as they ruined both the forest and had severe effects on wildlife and he wrote hundreds of letters protesting it. This shines through his writings in this book too.

Likewise, he also appears to have had a strong concern for knowledge and skills increasingly lost, something which of course today has gone even farther with the generations following, with the majority being completely incapable of handling themselves in the wild. The very same concern also seems to be on the increase currently with a growing longing for a return to a more natural life and a return of old traditions. As always human society evolves on looping cycles.

Alongside of Thoreau, Nessmuk is probably one of the strongest influences on modern preservationists, bushcrafters, preppers, survivalists, isolationists and other back-to-nature anti-business, anti-government groups, which is not bad for a 110# woodsman, cronically ill with effects of tuberculosis and asthma, but with a love for nature as strong as steel.

His last camping and hunting trip was taken in 1887, at the age of 66, three years before his death. It took him to Florida, camping at the Halifax River, hunting wild turkey and quail and fishing. Reluctantly he left, reporting his experience of his last trip to Forest and Stream. Sears had caught malaria while in Florida and his health quickly deteriorated after this trip. In early May 1890 he was finally laid to rest, buried among the hemlocks of his garden. By then he was a quite famous outdoorsman and Mount Nessmuk and Lake Nessmuk were both named in his honor. Coincidentally, The last of the Nipmuc tribe, the tribe who taught him as a child; Miss Mary Jaha also died the very same year, something which was noted in Forest and Stream:

It is a curious and striking commentary upon possible far-reaching influence of even the humblest individual, that thousands of readers of a journal of today should have owed the pleasure found in the writings of one of its contributors to the chance impress upon his character of an illiterate woods hunting Indian in the forests of Massachusetts more than half a century ago.

Forest and Stream magazine for June 26, 1890

His writings can be bought in print, but also read online here:

Sources

1. Sears George W. (1891, 2nd print / 2014): Woodcraft. A photographic reproduction facsimile. Cornerstone Book Publishers, New Orleans USA

2. Sears George W. (1891 / 1993): Canoeing the Adirondacks with Nessmuk: The Adirondack Letters of George W. Sears. Syracuse University Press, New York USA

3. Bond Hallie E. (1995): Boats and Boating in the Adirondacks. Syracuse University Press, New York USA

4. Bodine Mazie Sears (1942): Nessmuk – Nature’s Own. Wellsboro Gazette, June 4 1942 <http://www.joycetice.com/articles/msbnessmuk.htm> (20. March 2014)

5. Merritt Jim (1998): Wild Man Nessmuk. Field & Stream Magazine, Vol C11 No 10, Feb 1998. Times Mirror Magazines, USA

6. Abaitu Matthew De (2011): The Art of Camping: The History and Practice of Sleeping Under the Stars. The Penguin Group, England

7. Nessmuk Historical Marker. ExplorePAhistory.com <http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-3E2> (20. March 2014)

8. Deluliis Dan. (2008): Biography over George Washington Sears (Nessmuk). Pennsylvania Center for the Book <http://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/bios/Sears__George_Washington.html> (20. March 2014)

9. Sears George W. (1880-85): Nessmuk’s Adirondack Letters. Robroy <http://robroy.dyndns.info/books/gws/N.HTM> (20. March 2014)