Odin with his raven, bitten by Fenrir, on Thorwald’s Cross of the Manx runestones

It might seem a bit odd writing about old Norse gods and mythology on a blog that primarily focuses on nature, hiking and bushcraft, but living in Scandinavia, surrounded by locations, streets and structures that still carry their names and relate to their worship (1), and studying the old myths, it is striking how deeply they connect to both a complex contemporary culture and nature, both of which can be traced in the nature and culture of the Nordic countries of today. It all comes very… natural, especially when you are alone in the woods, hearing the sounds of the raven, the owls, and the wind, and nothing more. And understanding Nordic nature and having the skills to live in chime with it was integral to the Norse culture, while that understanding at the same time also is reflected in their beliefs.

Before we continue I would like to make a little disclaimer. I am far from an expert on the Nordic belief systems and while I have studied it to a decent degree, and have studied the Middle Ages of Europe fairly extensively, my thoughts below should be taken with more than a few grains of salt. I am speculating, playing with ideas, trying to look at larger perspectives with a very fragmented and by its very nature deeply ambigious material. So do not take this article too serious. I find the ideas intriguing though, and I hope a few of you will feel the same. It should also be noted that I am mostly discussing the Odin of the later Viking period, and not so much the grimmer Death and War God of earlier period.

Names, meanings and connotations

As most people know, Odin, the god who gave man his soul, has animal companions in the shape of two ravens and two wolves, Hugin & Munin and Gere & Freke. Additionally, two valkyrias, Hrist & Mist serve him the only thing he feeds off of; wine, an unusual drink in the Nordic countries of the time. For some time I have been quite intrigued by the deeper implications of the meaning of these names and there are many interesting connotations to them. Some of the associations that come to my mind are the following:

ODIN (Odin comes from Óðr, meaning Inspiration, Rage, Frenzy, Mind, Extacy, Poetry)

Desire for knowledge, self-sacrifice, wisdom, wit, cleverness, treachery, Kvasir’s blood, mead & poetry, wine, magic, sejdr, galdr, gender-crossing, transgressor, shape-shifting, criminals, the hanged, spear, war, death & the undead, the Wild Hunt, recruiting for the The Final Battle, self-sacrifice & dying, mutilated & flawed

RAVEN Hugin & Munin (meaning Thought & Memory)

Air, shoulders, messengers, intelligence & trickery, thought & memory, mind & heart, logic & intuition, mind & desire, spirit animals, war & battle, carcass, meat & blood, the undead, playfulness, brother of the wolf

WOLVES Gere & Freke (meaning Ravenous & Greedy/Audacious/Warrior), Garm & Fenrir (Marsh Dweller), Månegarm, Hate & Skoll (Hate & Betrayal/Mockery)

Ground, low, feet, anger, frenzy, greed, meat & blood, eating, war & battle, carcass, Hel & the Underworld, the Sun and the Moon, Ragnarök & the new age, brother of the raven

VALKYRIAS SERVING ODIN Mist & Hrist (meaning Mist/Cloud & Shiver/Shake/Quake)

Wine, spiritual sustenance, inspiration, disassociation, poetry, control of self, frenzy, madness, anger

Looking at connotations gathered from reading the sources and trying to look at the larger picture, I get a sense that there may be some structure with deeper juxtapositioning incorporated into the names and choices of animals. But before I go into that, I will talk a bit about Odin and his companions.

The paradoxical and flawed god-king

In earlier period, Odin and his valkyries had quite strong connotations to death and were far grimmer figures than in late period. The idea of the good warrior’s Valhalla was not developed yet and instead the world of the dead was a dark place. In Njal’s Saga, 12 valkyries, six for North and six for South, are seen before the Battle of Clontarf, making a weave out of the intestines of men, using severed heads for weights, and swords and arrows for beaters, with the weaving deciding the fate of the warriors. Clearly, the valkyries are here reminiscent of the Norns of Fate; Urd, Skuld & Verdandi. Völsungasaga describes seeing a valkyria as “staring into a flame”. Likewise, the raven and the wolf were common scavengers on the battlefields, so for a God of war and death, those animals would be natural companions. Noteworthy though is that Odin himself, unlike Thor, never fights any battles, not until Ragnarök, that is.

In later period, Odin is described as having two basic motivations for most of his actions and characteristics; his quest for wisdom, and his preparation for the final battle at Ragnarök where he will die alongside of Thor, Freyr, Heimdall and Tyr, and a new better world will be born. From this many other things stem; his struggles to gain knowledge, his self-sacrifice and hanging himself from Yggdrasil, (thereby, perhaps, connecting him to “hanged men”, i.e. convicted criminals), his connection to war, battlefields and thereby also the scavenging animals of the battlefields, wolves and raven, his testing the value and valor of men and so on. He is a god of both wisdom and of war, although the latter in a way seems more a responsibility than a choice, much like for a king or jarl. And becoming one of Odin’s Einhärjar in Valhalla had a distinct purpose that had nothing to do with being rewarded for being a great warrior, at least no more than the honour in having been selected to join an elite army preparing for the ultimate battle. Not a battle of his choosing though, but one he has to fight and has prepared for for many centuries.

Odin is often, with right, perceived as a dark, odd, unreliable and frightening god. So why does he fascinate so many today, especially considering that the Norse pantheon is so rich with many other more positive aspects that were important to our ancestors? Quite commonly, I believe, people are attracted to Odin due to his perceived greater complexity. The Odin of the late Viking period is simply seen as a lot more dynamic and difficult, far more so than most other gods, even to a degree that can seem paradoxical and contradictory, with perhaps Loki, or possibly Freyja, godess of both love and war, being something closer to it.

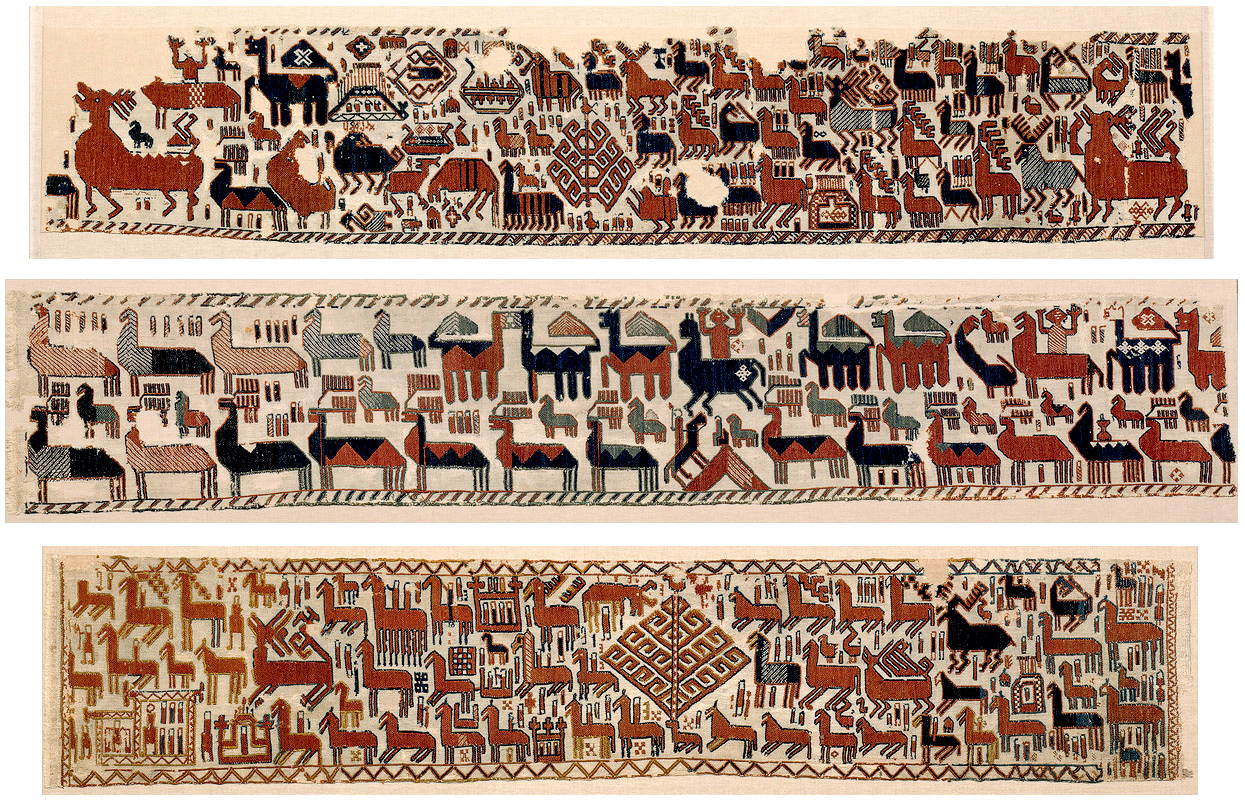

Three of the five 11 cent Överhogdal tapestries from Sweden, speculated to show Ragnarök with Yggrasil, the World Tree which Odin hung from, sacrificing himself to himself, in order to gain knowledge of the magic runes.

His search for knowledge, his sacrifices to gain it, his taking part in creating man as well as his knowing that he will die to create a new world and yet gathering an army of the best warriors to be able to succeed, his “disinterest” in wealth over honour, which matches the Norse culture in general, his trickeries and testing the valour of men, his intelligence & wit, his love and his poetic side, his dark sides revolving around death/spirits, and his magic, gendercrossing etc, etc make him more difficult and interesting to study than most other gods. And then the ambiguities, the oppositions and even flaws (at least in modern eyes) within the same character, combine into making him very interesting, almost human, and therefore, wrong or right, relateable. And the fact that the Norse gods have desires and drives that are similar to those of men, but are still limited in their powers, makes them far more interesting than the Christian god whose motives and actions man can’t apprehend as evil and bad things happen, despite God being all powerful. And perhaps similar motivations were not uncommon in the late Viking period.

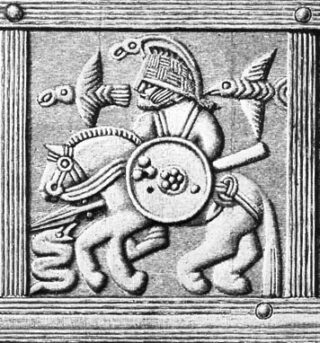

Believed depiction of Odin from Vendel period

Reading Havamal, the Song of the High (Odin) and the advice given therein, advice which to modern morality can seem wrong and even immoral, the mythical Odin of late Viking period often seems to fit well with the ideals expressed therein, which is of course not very surprising considering that it is his song. Many of the things that are associated with him tie in to a lot of ideals of the time, embedded into the whole culture. In my understanding of Norse culture, you should strive for honour and fairness, but at the same time there was no shame in desiring to be rich either, nor in seeking revenge for wrongdoings of enemies or traitors. Hospitality and kindness to strangers was vital and at the core of Norse culture, and yet raiding was perceived as a fair means of gaining land and wealth. Loyalty and reliability was hugely important, but treachery was also a fair tool to use when needed. Etc, etc.

As for the dark associations to his name, revolving around hanging, death and the undead, and spears, they weren’t necessarily exclusively negative ones in later Viking period. Quite the contrary. They were connected to his preparations for Ragnarök. The duality of especially Odin, not unlike with Greek & Roman gods, seems to connect to a “realistic” understanding of power that relate to contemporary society, while at the same time promoting certain ideals. In this understanding you have to respect and fear the power of the gods, while you at the same time can appeal to them. It’s very basic, much like you would with any man or woman with great power.

Possibly, Odin as the highest god (at one point and to some), the one who took part in creating man and ultimately also in saving man for a new world by having gathered a great army of men and gods, and knowingly sacrificing himself, also stands above concerns for simpler morality and laws that govern everyone else, gods and men alike. This has always been true for leaders of society, to varying degrees. Sometimes a good leader has to do bad things and it is not always easy for others to understand the motives behind, and for that reason, it is also difficult to judge and question the actions of a leader. In a manner of speaking, Odin is like a king or jarl in this, as he seems to often move outside of the society of both gods and men, but at the same time defining or mirroring the morality of the Norse culture.

All these aspects of Odin, (and Norse culture), can make him seem more than a little fragmented at times, which is perhaps not so surprising as the later written sources collected an oral tradition built over many centuries and probably created in many widely separated places, causing quite differing images of the same god. The same is true for the different perceptions of the afterlife. Adding the increased Christian influence, and the Christians who documented the system in their books, together with all the complex and confusing kennings. and things get really difficult… It’s a bit like trying to define what characterizes our modern culture by studying mostly foreign sources written over the last 300-400 years… It is bound to be contradictory.

The images of most gods and deities changed over time and there was certainly cross-pollination between cultures. That is one of the main differences to Christianity with its bible although the older roots of the Christian god certainly connect to older religions, and even the image of the Christian god changed drastically over the centuries, despite having a fixed text to help conserve it. Nordic culture seems to have had a rather pragmatic view on gods and spirits, although the deep connotations to values in the whole culture still made it fairly resistant to conflicting change, at the same time as the polytheistic nature of it made it vulnerable to the same. And the Norse myths and concepts adapted and changed, influenced by the monotheism and the trinity of the Christians.

***

So, having discussed Odin reasonably thoroughly, lets turn, finally, to his close companions.

The Ravens & the Wolves

Looking to the verses we are told that Odin’s ravens are sent out every day to fly around the world, gathering information to keep him wise and appraised, but also seemingly helping him search for the best warriors among those slain on the battlefields and hung criminals.

Huginn ok Muninn

fljúga hverjan dag

Jörmungrund yfir;

óumz ek of Hugin

at hann aftr né komi,

þó siámz ek meir um Muninn.Hugin and Munin

fly each day

over the spacious earth.

I fear for Hugin,

that he come not back,

yet more anxious am I for Munin.– Grimnismál

Two ravens flew from Hnikar’s [Óðinn’s]

shoulders; Huginn to the hanged and

Muninn to the slain [lit. corpses].

Odin and his ravens, from Sutton Hoo

Furthermore, Odin sacrificing an eye in particular, in order to gain greater wisdom and “insight” is quite interesting. In a way, weaker outwards gazing here creates a stronger inwards gaze, and the weaker outwards gaze is perhaps compensated through the help of his raven.

The ravens as birds are certainly also similar in character to Odin, being both clever and intelligent, but also in being tricksters that fool others and like to play games. The names of his ravens, Thought and Memory, are particularly interesting when we consider that he worries the most about the latter not returning as he sends them off into the world. It should be noted however, that aside from Odin’s companion ravens, the raven are often described as foul birds of death, covered in grime.

While the names of Hugin and Munin indicate mental and spiritual things, the names of Gere and Freke are clearly focused on the body, on raw sustenance, something which Odin doesn’t do himself directly, feeding on things Odin doesn’t care for, or alternately feeding on behalf of Odin.

Unlike Odin’s ravens, we are never really told what function his companion wolves serve. So why does Odin have two wolves as companions? Their names have to do with greed and gluttony etc, but those characteristics don’t strike me as particularly typical of later period Odin. Quite the contrary, despite knowing where all the secret treasures of the world are hidden, and knowing magic that can uncover them, he seems to be uninterested in such things, being far more interested in intellectual things, in knowledge, and the whole Norse culture seem to have valued certain ideals far more than worldly riches. On the other hand Odin is also in a way the great protector, gathering the best soldiers for the final battle at Ragnarök where he knows he will lose his life, alongside of fellow gods and einhärjar. He was a war god, perhaps not for a love of war, but out of necessity, as any good warrior chief, always on the lookout for good warriors that could assist him at Ragnarök.

Furthermore, the wolves are the partner of the raven in hunting and on the battlefields, although of the opposite, the earth kind. And they share a similar “cheeky” character. In fact, Freki, a name/word which is also used as a reference to the apocalyptic wolf Fenrir, also means just that; cheeky (Modern Swedish “Fräck”) and perhaps closer to the characteristics of a good warrior; audacious, bold. And looking to the older roots for Odin, the hungry wolves of the battlefields were of course a striking image to associate with a deity connected to death. So obviously they can both be regarded as just representatives of Odin’s war & death sides. But perhaps their names and the idea that Odin gives them all his food, instead living off of wine, indicates something more?

The Valkyrias

Hrist ok Mist

vil ek at mér horn beri,

Skeggiöld ok Skögul,

Hildi ok Þrúði,

Hlökk ok Herfiötur,

Göll ok Geirölul,

Randgríð ok Ráðgríð

ok Reginleif;

þær bera einheriom öl.Hrist and Mist

bring the horn at my will,

Skeggjold and Skogul;

Hild and Thruth,

Hlok and Herfjotur,

Gol and Geironul,

Randgrith and Rathgrith

and Reginleif

Beer to the warriors bring.– Grimnismál

Mist and Hrist are trickier as their names may carry meaning on their own, serving Odin with wine, a drink that helps blurring the sorrows of the world, but perhaps should also be considered together with the other named valkyrias (2) who often have more clear war-focused connotations to their names, in which case Mist/Cloud and Quake/Shiver take on a different meaning.

Looking at the verses we can see that the names of the valkyrias rhyme in pairs, following the form of the verses. It seems to me as if the oral tradition with rhymes also forced cleverness and creativity with names, sometimes even giving cause to multiple names for the same character, and perhaps with time also causing some changes in meaning. But while the “form” of Hrist and Mist rhymes here, the meaning of their names would likely still be relevant. True too that Hrist and Mist might not be fixed servants, as they are only mentioned once, but their names bring some interesting connotations with them. Perhaps the two are even to be considered a kind of opposites; “mist” as calm, blurry, slow and unclear, “quake & shiver” as in frenzy, madness and anger, and with Hrist and Mist, through the serving of wine, being capable of stiring quite different spirits in Odin.

Looking to Greek mythology, a belief system which the Norse belief systems clearly relate to, we find another god which is associated with frenzy and gender ambiguity, the God of Wine; Dionysos, and perhaps this explains why Odin is said to prefer wine and not as perhaps more expected, the poet’s drink; mead. And wine causing frenzy and madness would of course also fit a god whose name carries that very meaning.

Meaning & Juxtapositioning

The symbolism and meanings of words and names must have been quite conscious for a culture so focused on oral tradition. But over time words take on new meanings, sometimes from the stories that relate to the words and names, and other times the names take on new meaning from the words themselves, creating myths to explain those meanings. So, at the same time words can change meaning due to whom or what they are associated with as the latter changes. Consequently, the name Odin might have carried certain meanings originally, but could also cause its root, the word Óðr, to catch new meanings as the myth around Odin evolved over time.

That the names always carried meaning I think we can be fairly certain of, but what the connotations were for them is quite difficult to know now, even if we can draw some careful conclusions. The meaning of names was certainly important and chosen carefully, partly through kenning (cultural reference) and forced by need for strict rhyming that required a library of names and terms that could be fit to rhyme in improvised oral poetry, and the flyting, much like modern freestyle rap. And such juxtaposition of air and earth certainly existed both before, later and elsewhere.

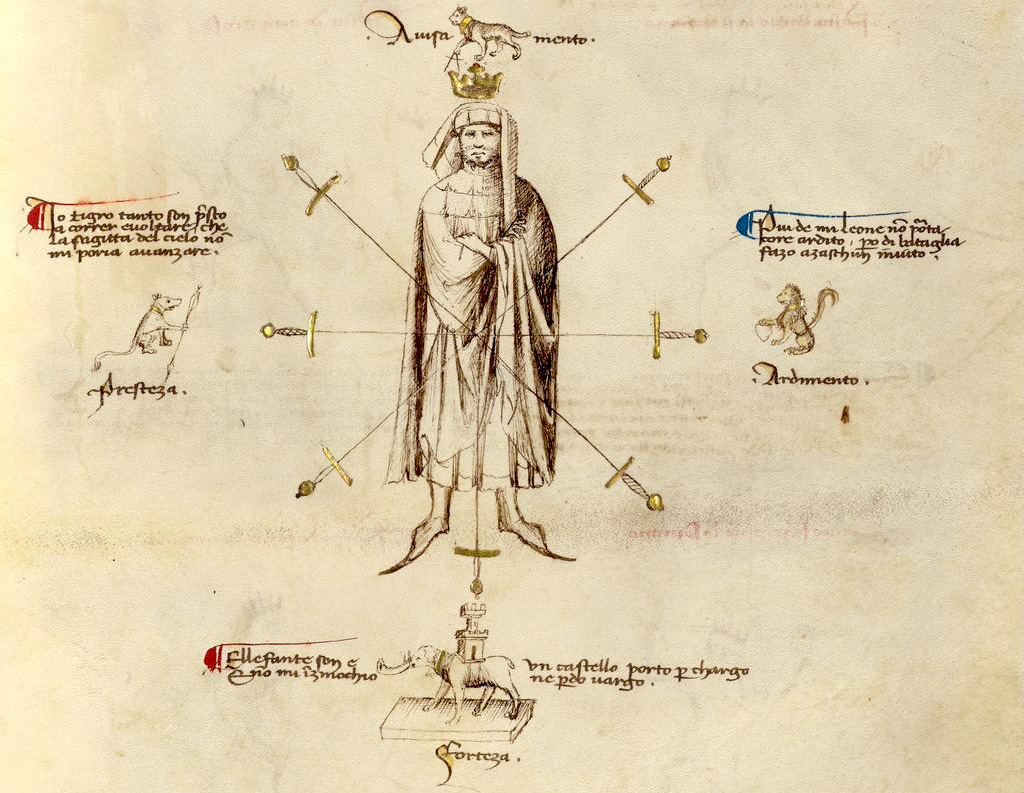

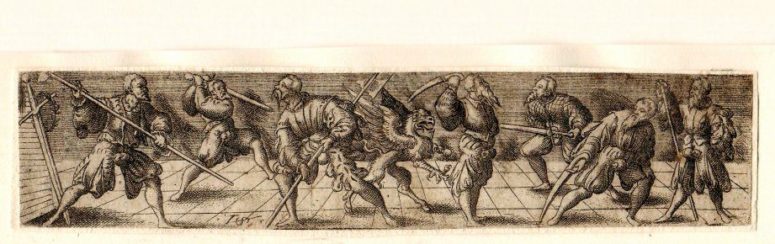

Image showing animal strengths suitable for a warrior. From a fencing treatise by Fiore Dei Liberi, ca 1404.

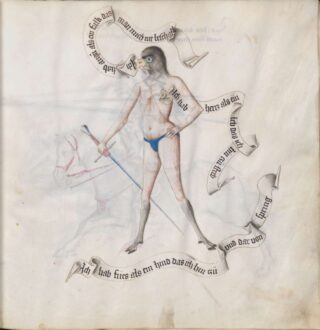

From Paulus Kals fencing treatise of 1470, a fencer with the head of an eagle and feet of a deer.

As for the oppositions of Air/Earth, High/Low, North/South, Spirit/Body, those ideas were certainly common concepts in the Middle Ages, as was the notion of assuming the characteristics or even spirits of animal. Looking to another topic that I have researched for many years, the martial arts traditions of Europe, we find several such concepts, for instance with Fiore dei Liberi in the early 1400s and in Paulus Kal about 60 years later.

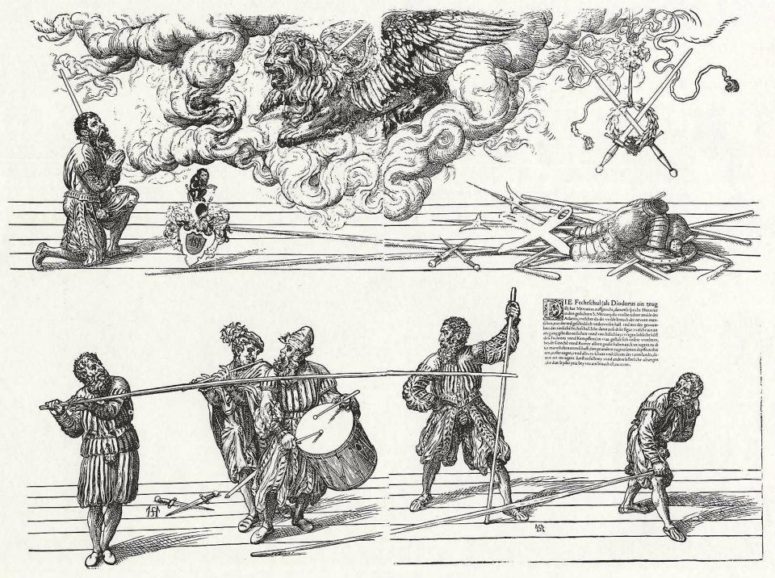

These ideas were also important to the fencing guilds of the Holy Roman Empire, where the Marxbrüder chose a winged lion, the symbol of St Mark for their guild, while the Freifechter chose the Griffin. The idea was to incorporate the characteristics of each of the animals that these mythical beings were composed of; lions and eagles, into their ideals for great warriors, choosing the Kings of the Air and Earth Beasts, respectively.

The Marxbrüder fencing guld, with their winged Lion of St. Mark.

The Freifechter fencing guild, with their Griffin, a creature half lion, half eagle.

These ideas were greatly evolved with alchemy and magic in late medieval and Renaissance Europe, borrowing material from the East, in places where the vikings too had visited, often and regularly. Man itself came to be considered as a reflection of the universe, seeking symmetry and perfect proportions with man, the planets and the divine. The physical and the spiritual worlds could both be evolved through alchemy and magic and the latter aspect was not least important to the alchemists. (3)

The Sun and the Moon fighting, with the opposition of Lion vs Griffin, and male vs female. In Norse culture the genders of the celestial bodies seem to have been reversed, with the Sun being female. From Aurora consurgens, alchemical treatise from the 15th cent

The Bronze Age Trundholm Sun Chariot, dated to 1800 to 1600 BCE

Some degree of juxtaposition of things we also know from Norse mythology, like Fire & Ice in Gylfaginning, describing the creation of the three worlds and the Serpent & the Eagle at the root and crown of Yggdrasil described in Völuspá. The Valkyrias of the North and South of Njals Saga also come to mind, as do Fenrir’s offspring, the wolves Hate (Hating) and Skoll (Mocking) who chase the Moon and the Sun (4) and the horses Skinfaxi (Shining Mane) and Hrimfaxi (Frosty Mane) who pull day and night over the world. And Air, Sea and Earth, Wood and Metal were probably all regarded as something akin to the “Elements” of other cultures, i.e. the things that the world was made up of.

The raven and the wolf come from different elements; the air and the earth and there appears to be a juxtapositioning between the two, as possibly indicated by their names, with the raven as something ethereal, high, of the air and spirit, and the wolves as corporeal, low. Odin seems to be inbetween these two, taking “nourishment” from both, but mostly from the ravens, although in war, the Audatious (Freki) would be useful as also reflected in the Úlfhéðnar and that meaning matches the warlike connotations of “frenzy” or “mad” for Óðr. And possibly Odin’s valkyrias Hrist and Mist are to be considered opposing pairs, with their capacity to stir different spirits in Odin through the serving of wine.

So does all this match up and have any validity? I honestly don’t know. I don’t think names were chosen at random or without great care. However, understanding those names and words and the connotations associated with them is tremendously difficult, not least as the words themselves appear to have changed meaning due to the associations gained from the myths that evolved around the deities that were named from those words. There appears to have been a mutual exchange between the meanings of the words and the characteristics of the deities and it is difficult to know the order of the “hen and the egg” here. So, in the end this has all been a playing with ideas and thoughts, although, I hope, an interesting and entertaining one.

Notes

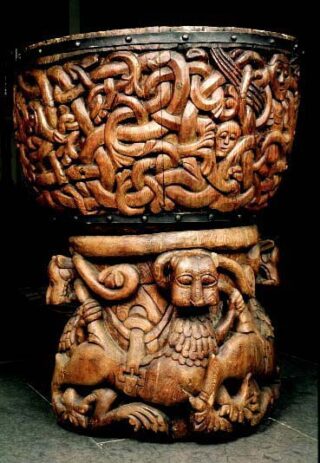

The 12th cent fountain from the old church of Alnö, Sweden

1. Old Norse words are everywhere in the Nordic countries, of course in the names of the days of the week, and especially, and often semi-forgotten, in names of many locations, but also in names of modern buildings and streets. For example, I grew up in the centre of an island in the north of Sweden, in a place since viking times called Wii, the Norse word for “place for sacrifice”. Two other places, Hovid and Hovberget both relate to “hov”, another word for “place for sacrifice. A close location was Vindhem (Wind Home) thought to be an old harbour. My parents married in a 12th century church and I was baptized in the equally old baptismal fount from that church, a fount carved out of wood in traditional Nordic style, as seen to the right.

For several years after having moved to Gothenburg on the west coast of Sweden, I lived near Ramberget (Raven Mountain) and today I live near the public sports centre Valhalla (Valhalla is actually one of the stops on my tram ride…), near a square called Odinsplatsen (Odin’s Place), close to streets named Friggagatan (Frigga’s Street) and Baldersgatan (Balder’s Street) and a sports arena named Ullevi (Ull’s Place of Sacrifice).

2. The names of the other valkyrias in this verse carry the following meanings:

Skeggjöld = literally “beard-age” referring to bearded axes, thus axe-age.

Skögul = “Shaker”or possibly “high-towering”

Hild = “Battle”

Thruth = “Strength” or “power

Hlok = “Noise, battle”

Herfjotur = Host-fetter” or “fetter of the army

Gol = “Tumult” or “noise, battle

Geironul = Uncertain; possibly connected to the Odinic name Geirölnir. Possibly meaning “the one charging forth with the spear”.

Randgrith = Shield-truce” or possibly “shield-destroyer

Rathgrith = “Council-truce” or possibly “the bossy

Reginleif = “Power-trace” or “daughter of the gods

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_valkyrie_names

3. For more on this you might want to read some of the following articles:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermeticism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alchemy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_(paranormal)

http://hroarr.com/the-rose-and-the-pentagram

4. See e.g. the article on Skoll and Hate at Norse Mythology for smart people.